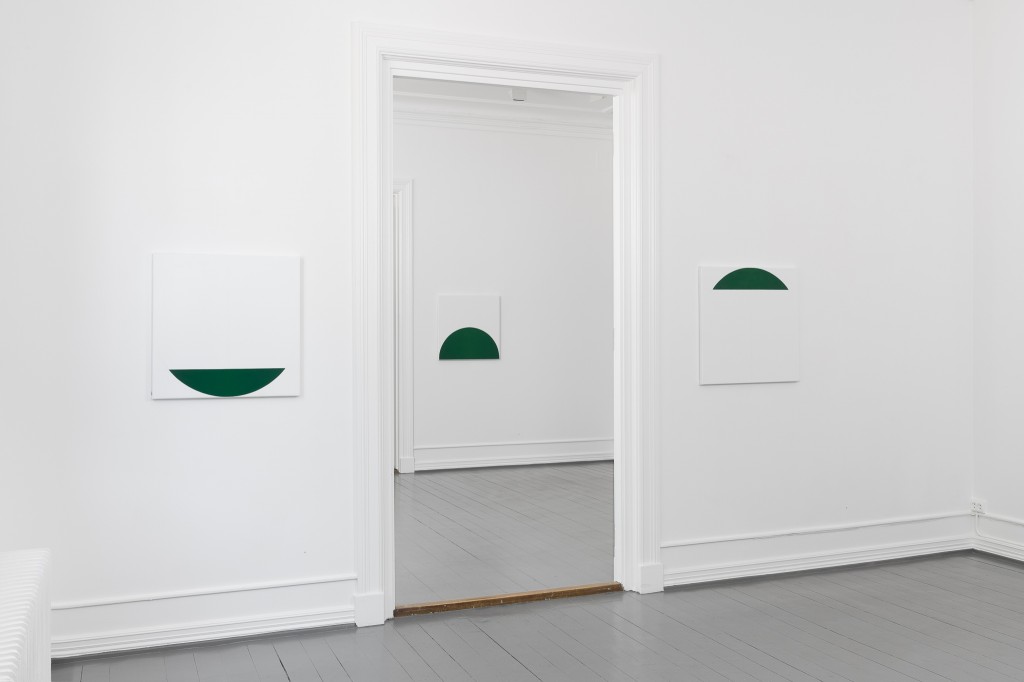

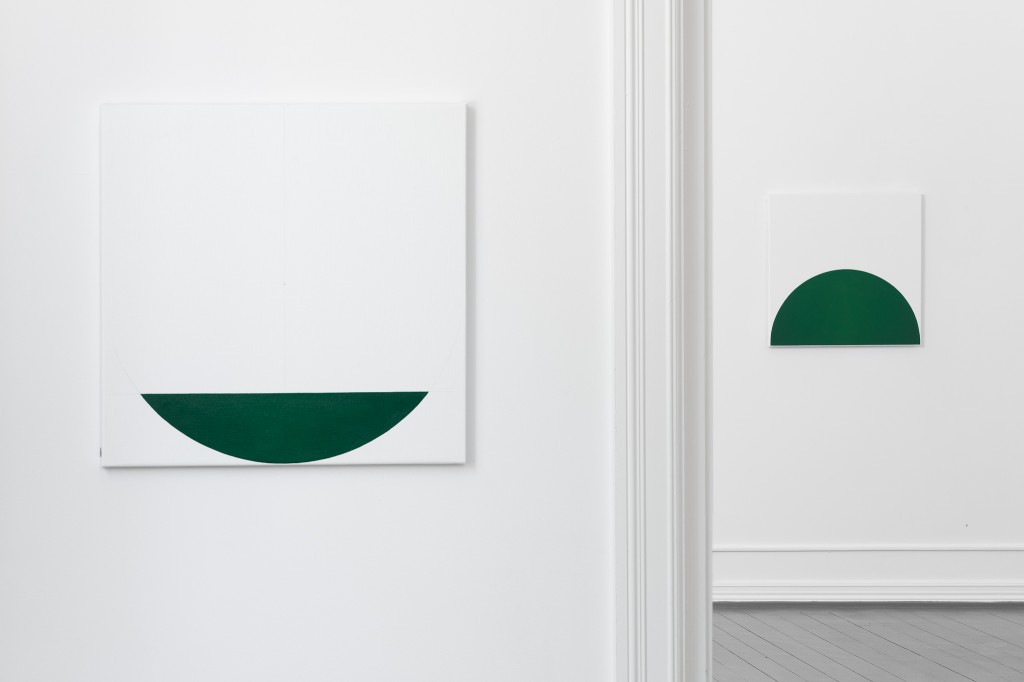

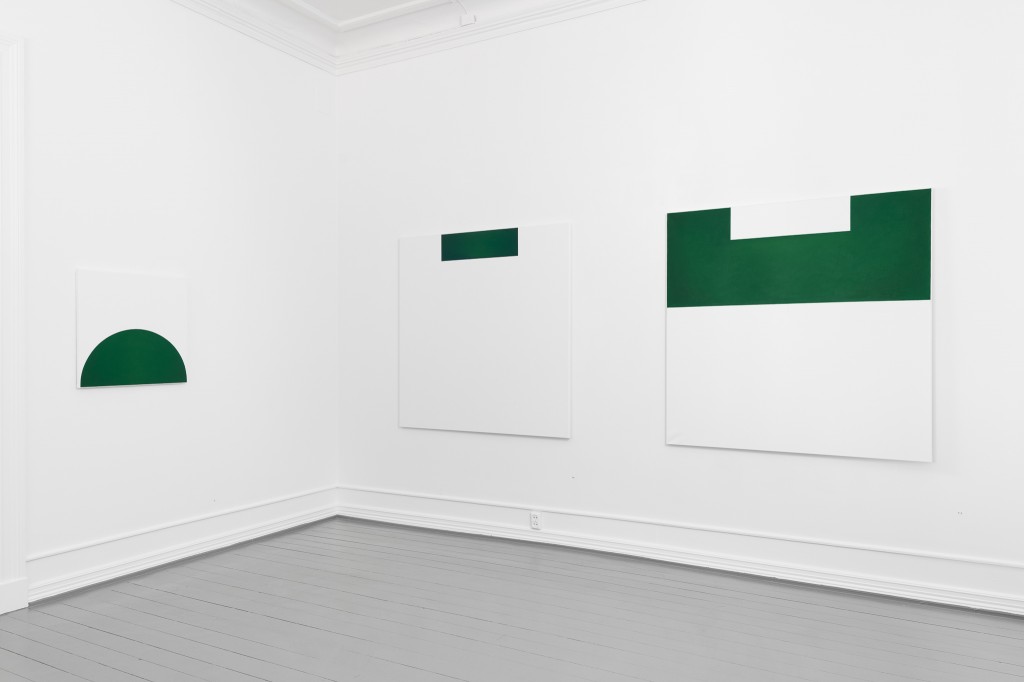

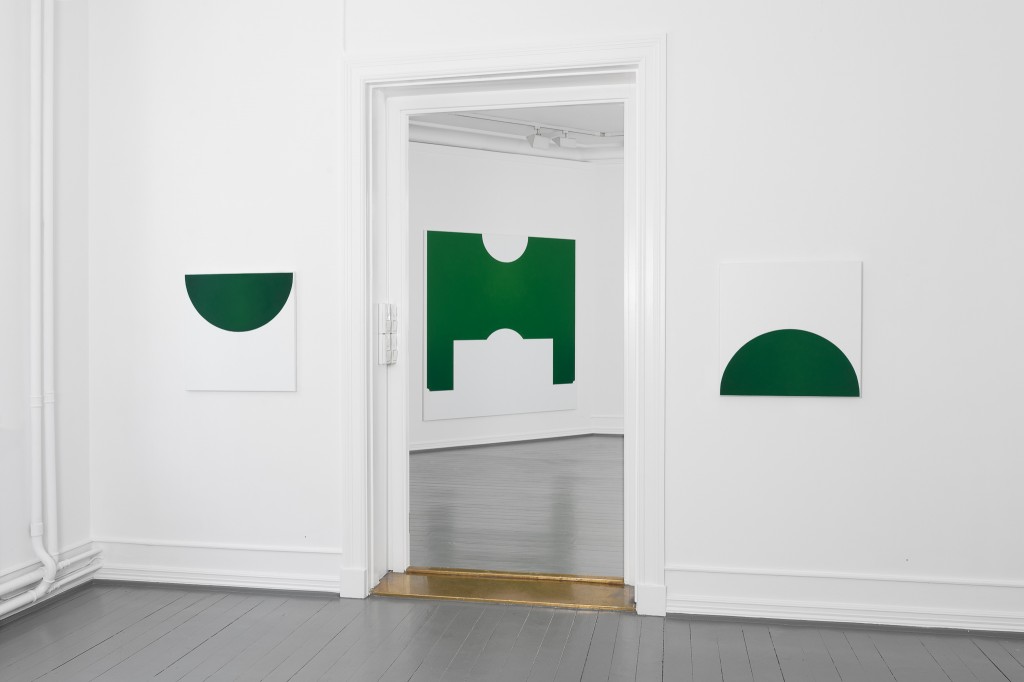

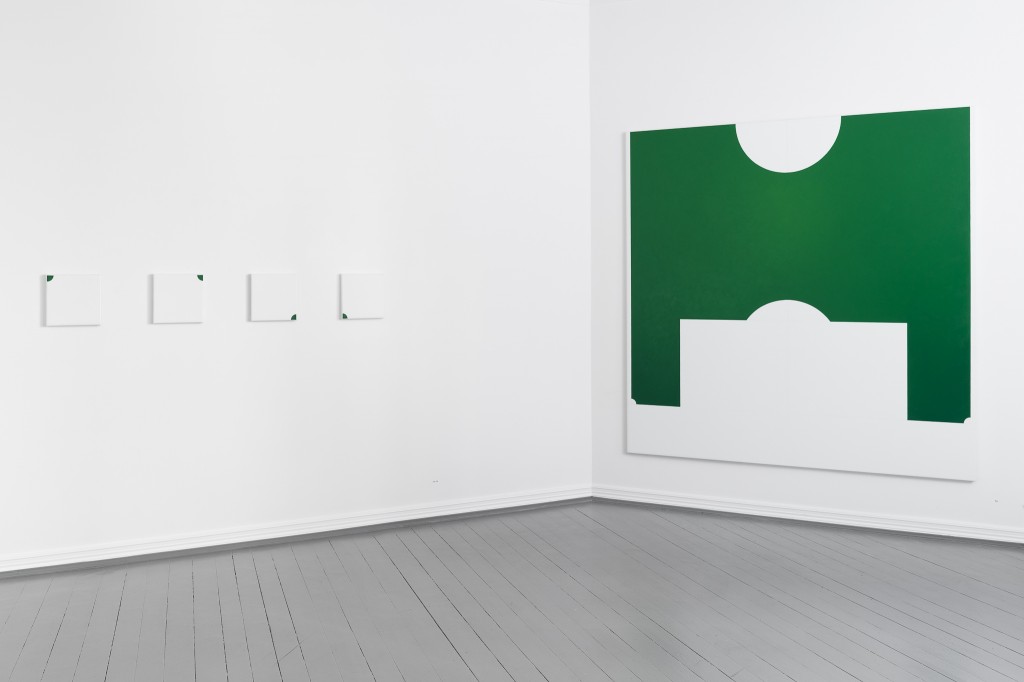

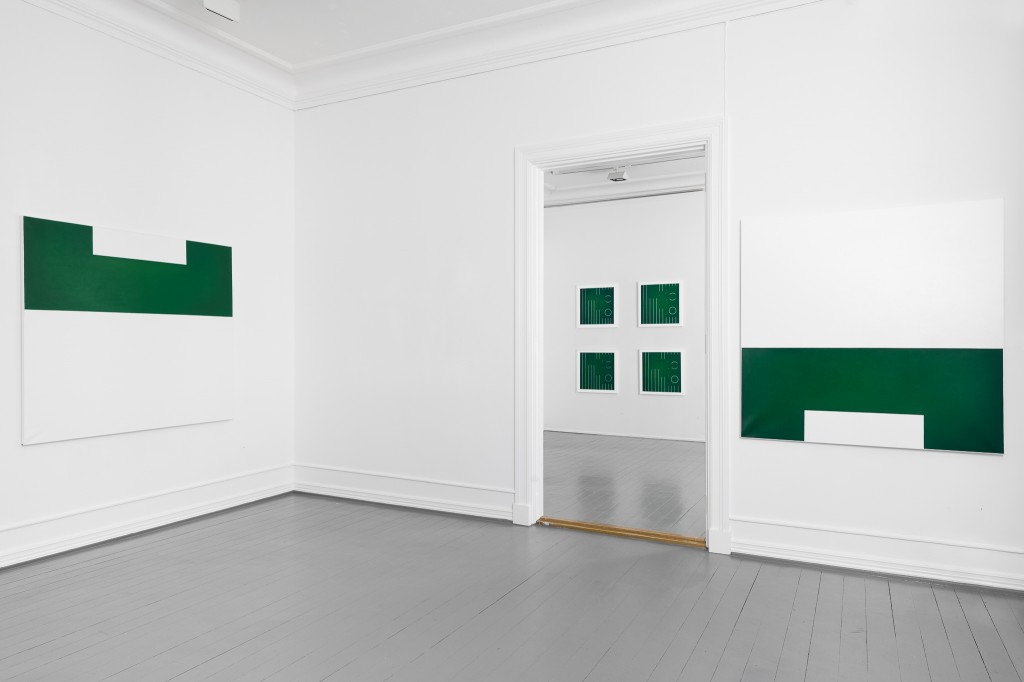

Gudenes Felt at LNM

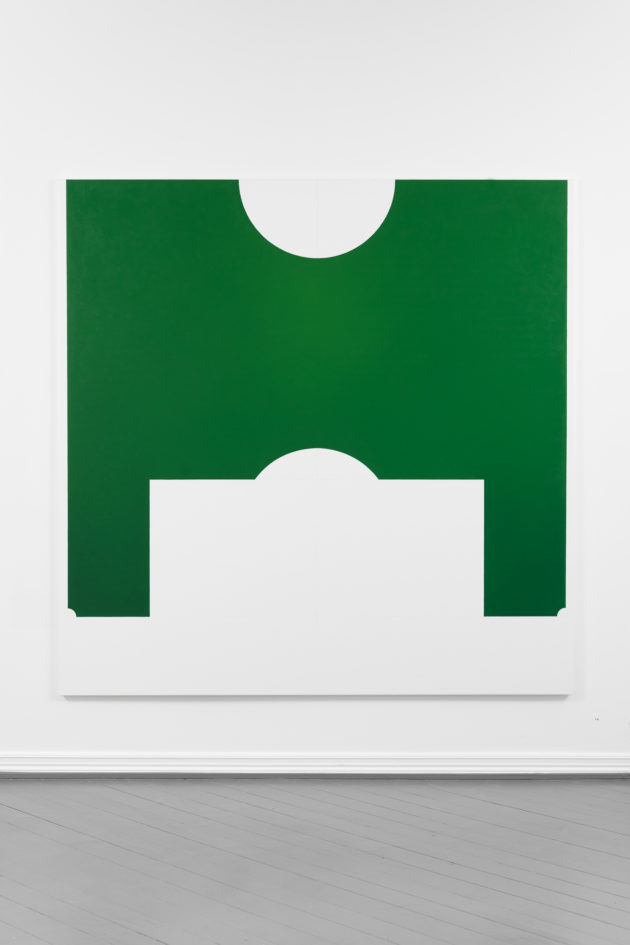

Green on white I – XIV

oil on canvas.

Highbury, La Bombonera, San Mamés, Maracanã

oil on canvas, 60 x 60 cm

A sidelong glance, with suspicion

Gertrud Sandqvist

Hanna Sjöstrand works first and foremost with painting. She uses techniques approximately as one would before photography existed. If she wants to explore something in the form of an image, she does it with painting.

One of the consequences of the many ways in how music can be produced today—that is, music coming not from instruments or the human voice—is that we recognise that the origin of the sound’s sensuality might not come from something obvious to us. The wood of an oboe, the brass of a trumpet, the shape of a violin’s chamber—not to mention the bodily nature of the human voice—became qualities in and of themselves only when we could hear alternative sounds not made by air passing through bodies or materials.

Something similar happens when one today works with ideas, or even realitistic depcitions, in painting with paint, brush, and surface. The inherent sensuality of the material rubs off. This fact fascinates Sjöstrand. In the series of paintings she has been working on recently about the game of football, the green colour she typically uses for her schematic descriptions also carries the memories of the green nuances that have been used to depict grass. The grassiness of the football field rubs off on the rule system. The odour of the oil paint carries streaks of fresh foliage. But the focus is on the game and the game’s rules, as well as its history.

Football seems to have been a wargame, or a diversion from war. So it was in China over two thousand years ago and, according to Tomas Lappalainen (1), in the Greek city states of antiquity, so one could assume it still works this way today judging by the emotional intensity surrounding the game.

Using the term “war,” one should not here understand it from the point of view of state politics but rather the violence and ultraviolence that takes place between groups outside the state or in its absence, which are organised around violence, humiliation, and revenge. Lappalainen cites the author Milovan Djilas:

Revenge is an overwhelming and all consuming flame. It sets fire to and burns up all other thoughts and feelings. … Revenge—it is the breath of life we share with our clan members, revenge is eternal both in good times and bad. Revenge was the debt we paid for our forefathers’ and clan members’ love and sacrifices. … It was the embers in our eyes, the fire in our jaws, the blood pounding through our temples, and the words that turned to stone in our throats when we learned that our blood had been spilled. … Revenge is not hate, but rather the wildest and sweetest form of inebriation, both for those who must carry it out and for those who will be revenged.

Anyone who has witnessed the passion and rage of football supporters can recognise this description.

Hanna Sjösrand is not one of those drunk on revenge. I suspect that many in the cult of football remain a mystery to her, just as to me. That is why I am so fascinated, just as when one has tried to follow countless matches with a sidelong glance, in wonder.

The rules of football were set in stone in 1863 at the Freemason’s Tavern in London (2). Already here it gets interesting. A freemason’s hangout! In some shady way, the Freemasons seem to have something to do with football. What is the connection, other than the sense of a somewhat secret brotherhood? The Freemason’s Tavern was the Grand Lodge of England’s meeting place, the capital of Freemasonry, that mythical and mystical society. What does it mean that the Football Association was founded there? The careful rules of the game established were called “Laws of the Game.” These laws secure all proportions between the football player’s trajectories and the area they take place. If there is some Freemason interest here, it must lie in the proportion of this meeting place, just like in the proportions of the universe—the unseen, created by the Great Builder.

One of Sjöstrand’s paintings, enigmatic in its severity, orders up the lines and half circles of a football field. Outside of this context, it reminds us now of a ritualistic pattern, or perhaps a musical composition—for cymbal, or maybe lyre?

Football is supposedly the world’s most popular sport, practiced by hundreds of millions of people. Why? Has it something to do with the rules themselves, the exercise, the ball with its pentagons, something that arouses an age old recognition? Sjöstrand dissects the visual, the formal, conditions without giving answers. She brings forth images that are beautiful in their strictness, that remind us of fields of ritual sacrifice, but she never solves the riddle. Why in the world do all these people, maybe all told a tenth of the earth’s population, engage in this sport so gravely, so intensely?

It could be that Ludwig Wittgenstein was thinking of football when he wrote his famous reflections on game rules in Philosophical Investigations 1953 (3). Or maybe he was thinking of tennis. Or cricket, to name another sport with harsh rules that mean all or nothing. Maybe art. Or wordplay.

83. Doesn’t the analogy between language and games throw light here? We can easily imagine people amusing themselves in a field by playing with a ball so as to start various existing games, but playing many without finishing them and in between throwing the ball aim- lessly into the air, chasing one another with the ball and bombarding one another for a joke and so on. And now someone says: The whole time they are playing a ball-game and following definite rules at every throw.

And is there not also the case where we play and—make up the rules as we go along? And there is even one where we alter them—as we go along.

219. “All the steps are really already taken” means: I no longer have any choice. The rule, once stamped with a particular meaning, traces the lines along which it is to be followed through the whole of space. ——But if something of this sort really were the case, how would it help? No; my description only made sense if it was to be understood symbolically. —I should have said: This is how it strikes me.

When I obey a rule, I do not choose.

I obey the rule blindly.

Here Wittgenstein describes the tragedy of man. Play becomes rules, and rules are followed blindly.

Hanna Sjöstrand cites the Laws of the Game in awe. Maybe similarly as Virginia Woolf: taking a sidelong glance, with suspicion.

Translator’s notes:

Wittgenstein quotes are from the English translation by G. E. M. Anscombe, 1958 edition, Basil Blackwell Ltd, Oxford.

NOTER

1. Lappalainen,Världens Första Medborgare, 2017, ss 44-45

2. FIFA Spelregler för fotboll

3. Filosofiska Undersökningar, översättning Anders Wedberg, Thales 1992

Documentation: Istvan Virag